“I think it's a field that gets more and more precarious because somehow work can be shifted around. Everybody becomes more and more of a designer and I think there's a lot of time pressure. Because there's enough people in design it seems it can continue that way. But of course, it's not healthy for anybody really. It impacts the quality of the work that comes out of it. You can cover it up, but [design] starts to suffer.”

“The current state of design is definitely way better than when I started because there’s now a value to design and everyone understands how it’s as important as an ad or the product you’re selling. And what happened lately with Virgil and democratizing it to a next level, that sort of diversity is opening up…it’s definitely way more accessible, easier for younger designers to come in and out.”

4.1

TECHNO-INSECURITY

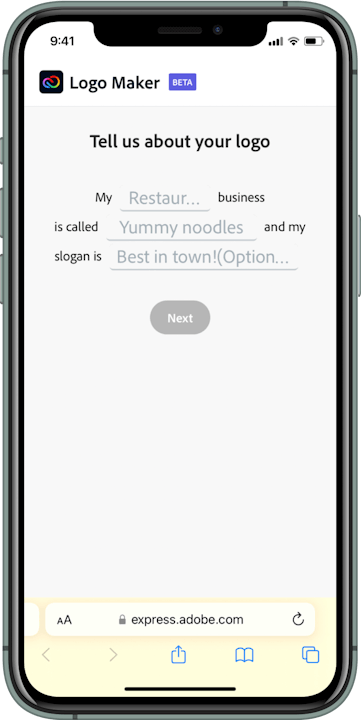

“[WHAT WORRIES ME IS] THE ASSUMPTION THAT ANYONE

CAN BE A DESIGNER IF GIVEN A TOOL TO DO SO.”

“Now there are many open source tools and communities where people can share tips or knowledge. So it's getting more accessible and easier to design. I think open source things like blender 3D represent how the industry is changing.”

“I'm really interested in the democratization of design. I want people to know you don't have to have a $60,000 degree to learn and be excited about design. Tools like Figma are opening design to different methods of making that cost less.”

“In design, like every other industry, every paradigm that has existed is sort of being shattered right now. So the bar for being able to get into design is lower than it's ever been before. There is so much technology and programs out there. So many tutorials, so much inspiration. It's never been easier to get into design and to contribute on a global stage as a designer.”

AND HIGH COMPETITION:

“I will say one anxiety has been with technology. There's so much appetite for design, and everyone wants it faster. So we have all these new tools available, but our timelines are getting shorter and expectations are higher.”

"Our work is less valued and generic and mediocre design is getting praise. Everything becomes more and more fast and low quality."

"Any fast tutorial video on TikTok represents the state of design for me."

"[What worries me is] lots of competition. Low prices. AI. Lots of DIY design apps. The recession."

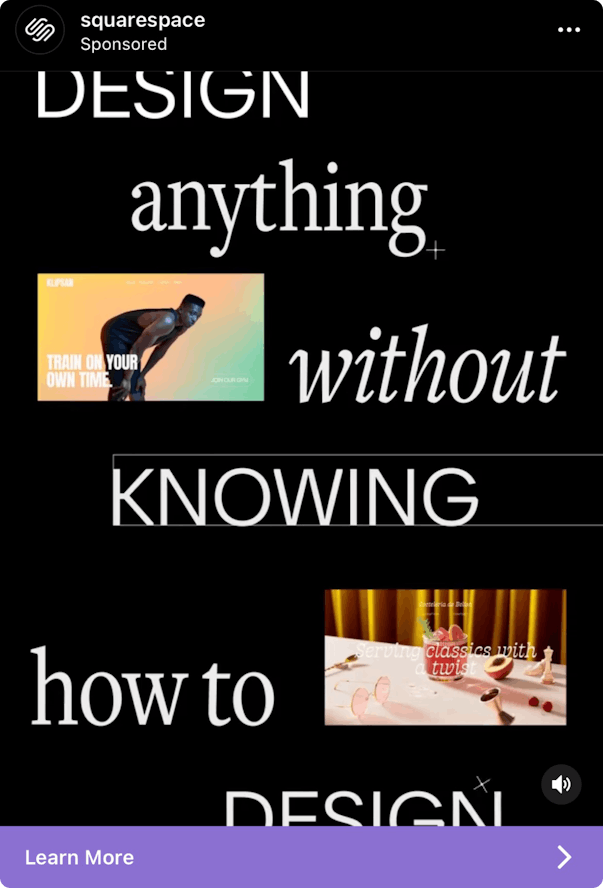

IG SPONSORED POST, SQUARESPACE

4.2

DECENTRALIZED DREAMS

“[I THINK A CHALLENGE IS] DESIGNING FOR AN

ACCESSIBLE INTERNET IN THE AGE OF WEB 3.0,

AND DESIGNING FOR A SAFER, FREER INTERNET

IN THE AGE OF INFORMATION AND DATA

COLLECTION.”

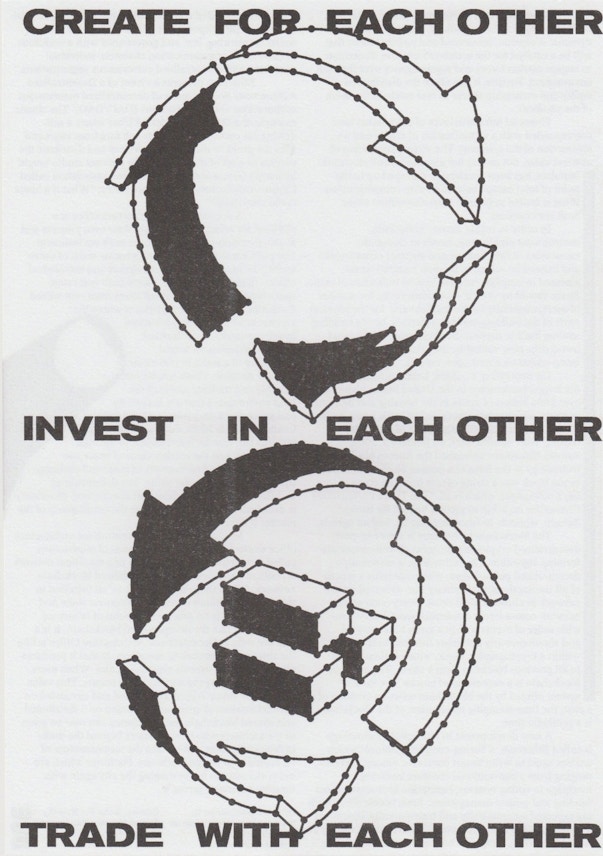

“NFTs provide many designers, photographers, and artists autonomy about their own work. And I think that's really great and exciting. It helps them make money.”

“I’d say I’m pro-NFTs because of all the possibilities it brings to the table. But we cannot be too naive about them.”

“I understand the access and the opportunities it brings to certain people and certain designers. I like how it makes them able to create more and make more profit out of their work.”

"I'm pro NFT. I think it's a way to be more proactive with our money. Something exciting and creative to sell our work."

“[What are the challenges that worry you today as a designer?] I would say NFTs in general, or the metaverse, but I still don’t know what to think about them. I see a lot of designers, artists, and companies pushing that way, without considering the positive or negative consequences.”

“I feel NFTs are a bit too trendy. They're interesting, but there’s just too much buzz right now. There are more interesting and meaningful things happening.”

[What object describes the state of design in 2022?] “A lego tower made of different colored bricks. While it may look like something creative, it lacks any kind of elegance or thinking. We just keep building and picking up any piece that can fit, chasing for the next best thing (web3, NFTs, etc.) when in reality it's just sloppy.”

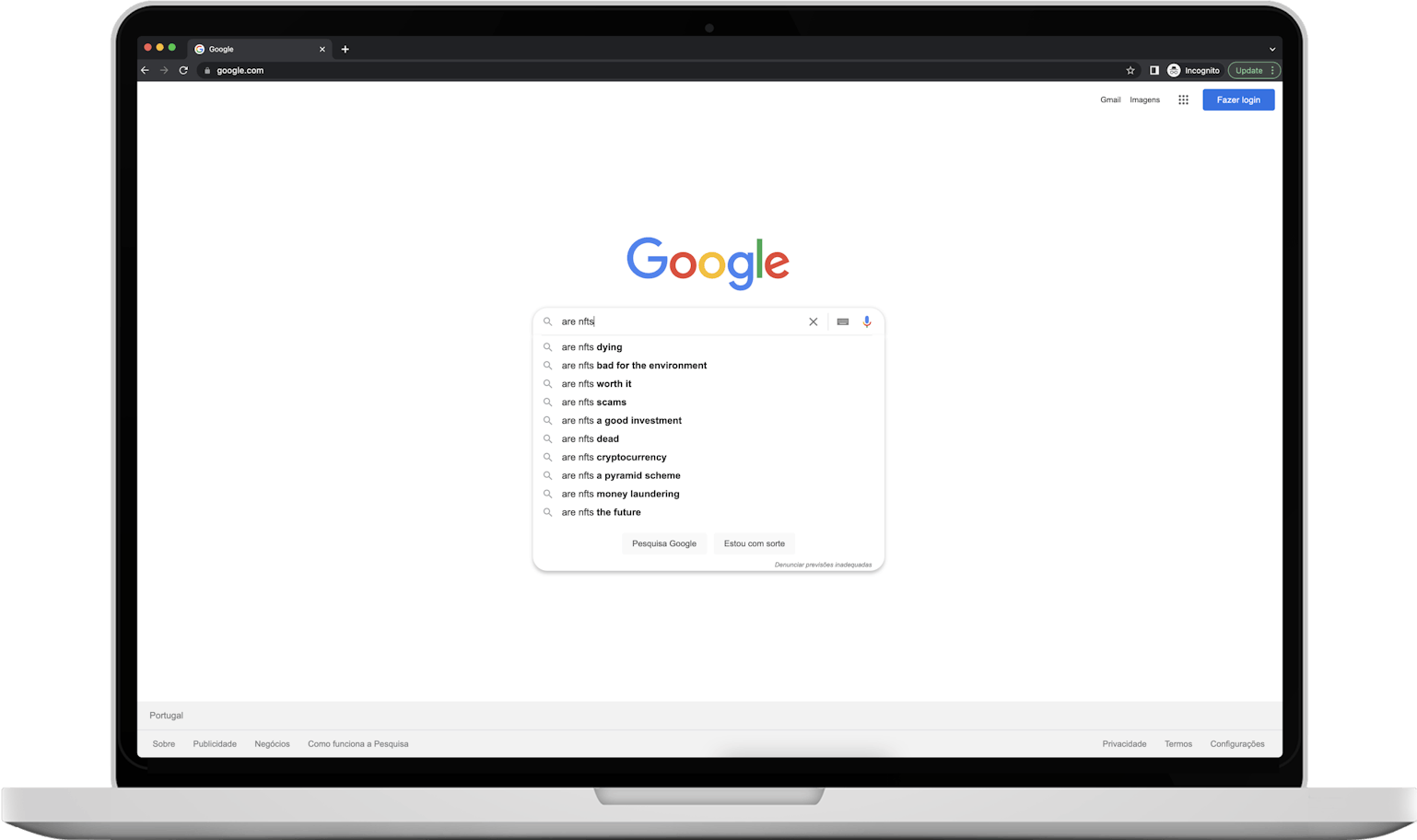

ARE NFTs...

4.3

ONE WITH THE MACHINE

“WHAT ARE YOU GONNA BRING TO THE TABLE NOW

THAT A COMPUTER CAN (ALMOST) DO YOUR JOB?”

IMAGE RESULTS FROM DALL-E PROMPT OF OPEN CALL RESPONSE:

“IT’S REALLY GREAT LOOKING POINTLESS BAG OF GLITTER AND GARBAGE”

“Will AI overtake my job? How do I keep my competitiveness?

"The machines will probably replace most of our work. How to be relevant to survive what is coming in the future has been constantly on my mind."

“There is a new aesthetic that's coming and I don't know how to describe it. I remember scrolling through people's mid journey explorations and feeling there is something kind of scary and haunting about the images, especially with distorted faces. But there's also beauty in it”

“Any kind of new technology won't replace us, it'll just change our role. These things are really getting smarter, giving us more time to spend on thinking about the problem or trying out more iterations. So I think the work will only get better. There's obviously a lot wrong with AI, of course, like inherent bias and plagiarism. But it's good to be cautiously optimistic.”

“With AI I’m curious to see if being a designer will become more of a passive role because you’ll be more directing and letting AI work for you.”

“I think technology will give creatives more tools to play, but if they’ll use those tools the best way is a different conversation. Take Photoshop: it eases up the work and lets you focus on what matters. Cropping an image used to take 5 hours and now it’s 3 minutes. To me it’s all exciting; I'm learning about them and also wondering how that will resonate with my 4-year-old son.”

“I think as designers working with AI you'll be freed up to do more creative thinking and less execution. It's going to be about the taste and the idea rather than the technical skill. Maybe the role of the illustrator is going to be about figuring out what the idea should be.”

FROM 50 DESIGNERS FROM AROUND THE WORLD

LINKS

“Let the Working Class In”

NDA Podcast

“Do Androids Dream of Balenciaga SS29?”

Robbie Barrat & Arabelle Sicardi

“Queer Dreams of an A.I.”

Riccardo Righi & Lucas LaRochelle

“Insert Complicated Title Here”

Virgil Abloh

“Could DAOs alter the makeup of our industry?”

Emily Segal & Lucas Mascatello"

The DALL-E 2 Prompt Book

10 free websites that are so valuable they feel illegal to know (a thread)

“Machine Learning: are designers even needed anymore?”

Alif Ibrahim